I’ve gotten used to answering the question “Where are you from?” My standard response is, “Well, I moved around a lot growing up. I lived in 14 different places in 12 different states before graduating high school.” My family moved a lot due to my father’s job, which took him to rural areas with limited resources.

I am, therefore, a product of the American public education system, from kindergarten to college, mostly in small rural schools. Some were better than others. All had dedicated teachers trying to do the best they could by their students with the resources they had. I became very good at being the new kid. I also watched a lot of public television (E-TV it was called back in the day) because at the time, NOVA came on everywhere, after all.

Perhaps because of all those NOVA episodes, I was interested in science early on; yet the only scientists to which I had direct exposure were the family doctors and Mr. Spock, from Star Trek, whom I only saw occasionally if there were just the right weather patterns to allow the rabbit ears to pick up the odd rerun on whatever non-public TV channel served the area we were in at the time. So, by age 8, I was answering the “What do you want to be when you grow up?” question with “I want to be a doctor.” That persisted until eleventh grade, when I was recommended for a summer science experience at Western Carolina University supported by a public scholarship so my parents didn’t have to pay anything for me to attend. “Well,” they said, “you should go do that.” And I did, and there I discovered physics for the first time.

I came away from this experience wanting to study physics and wanting to go to college. I really didn’t know how to do either. I did well in high school, and the western North Carolina mountain town school I was graduating from gave me a great education. However, it was definitely not a feeder school for elite higher education, and neither were the other two high schools in rural South Carolina and Wyoming that made up my transcript. We didn’t have tutors, and we didn’t have SAT prep classes. But at the public library I found a book about the test which fueled my hope that if I could do well on that exam, I might be able to demonstrate the ability to learn on a level playing field, which might open the door to college, where I could study physics. It worked.

I’m one of those individuals who did well enough on the SAT to get recognized when the rest of my transcript and background might not have otherwise caught anyone’s attention.

With the opportunity to attend the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill (UNC-CH) via the Morehead Scholarship, I immersed myself in physics. It was wonderful and opened a whole new world—in fact, the first three papers on my CV are from atomic collision experiments conducted at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. My plan was to continue studying physics in graduate school, until one gorgeous summer Carolina day after my junior year of undergrad. I found myself in the basement of Phillips Hall on the UNC-CH campus—alone, in a dark room—with instruments lit up and beeping like the Starship Enterprise. I realized in an instant that I didn’t want to do that. I wanted to be more connected to people and to help them if I could, as my father had. I wanted to go to medical school.

So, I left the basement for medical school without ever having taken a college biology course.

Once again, I learned there was a test I would need to take to get into medical school, the Medical College Admission Test, or MCAT, about which I knew little. But, there was a library, a book about the exam, the opportunity to prepare and the hope of a level playing field.

It worked. Again.

I did well (particularly well on the physics section) and as if lightning were striking twice, I was noticed by schools that might otherwise not have considered me.

The Mayo Medical School (now the Mayo Clinic Alix School of Medicine) offered me a scholarship and I saw firsthand the importance of a mission-driven organization. Mayo embodied the notion that “the needs of the patient come first,” and I wasn’t going anywhere else.

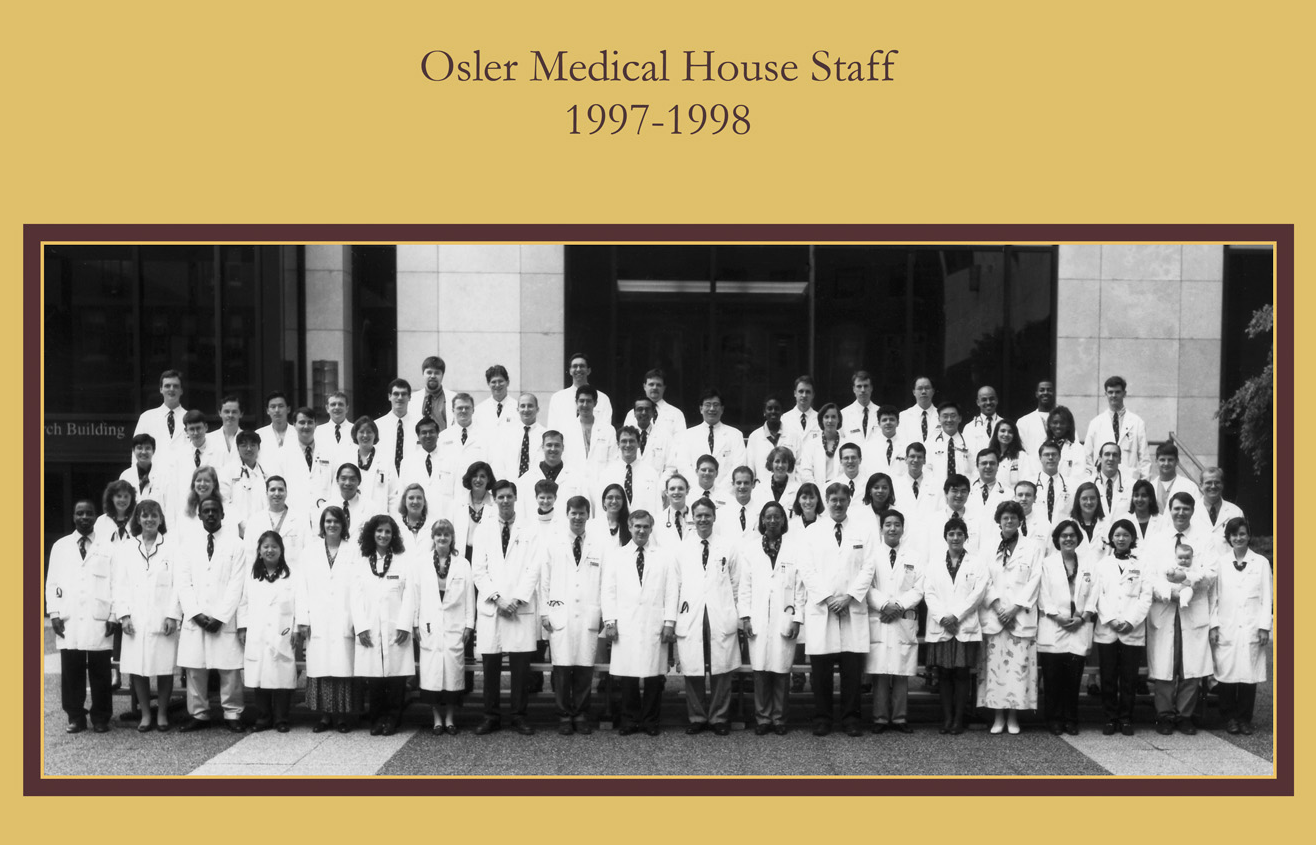

I matched to the Osler Medical Residency at Johns Hopkins Hospital for my internship, being attracted to the institution because of its grand history and reputation for training internists. My now wife was still in the MD/Ph.D. program at Mayo, and when she said yes to my marriage proposal, I returned to Mayo Clinic to complete residency and chief residency, and later joined the faculty.

While working there full-time as a hospitalist, I pursued my interest in epidemiology, biostatistics and medical education research by earning a Master of Public Health from the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health through the then-novel distance learning program. I was honored to become program director just as the Mayo program was entering the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Innovations Project, investigating new ways to train and study what we were doing in graduate medical education (GME) and how it might connect to patient-relevant outcomes. This would become the primary question of my scholarly career.

My wife and I were doing well in our respective careers, and overjoyed at our growing family—though things weren’t always easy. In 2011, my mother-in-law was diagnosed with breast cancer and lived with us for a year in Rochester while she was being treated. Introspection is an understatement, as this prompted my wife to shift her focus and pursue a breast radiology fellowship at the University of Washington in Seattle, leading to an offer to join the faculty at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia for a position combining her clinical and research abilities not available anywhere else at the time.

What do you do when your partner lands an opportunity like that? You do whatever it takes to help them achieve it.

So, in May 2013, I let my chair of medicine know I would be leaving the Mayo Clinic after nearly 22 years of training and practice. He and all the Mayo family could not have been more supportive. For several months, my primary focus was ensuring a smooth transition for the residents and the residency, and for my family to move.

My plan was to take care of our four children, two of whom had not yet started school, and to support my wife in her career.

However, within a couple weeks of arriving in the Philadelphia area, a longtime professional acquaintance contacted me from ABIM, where they were looking for someone who could help with initial certification and GME. Since 2014, I’ve had the pleasure of continuing to work with the internal medicine GME community, expanding the connections from the core internal medicine residency program community to include the training communities of all of ABIM’s 20 subspecialties.

In retrospect, being at ABIM feels like where I was always meant to be. Standardized testing afforded me so many opportunities that otherwise would have been unavailable—including the new role I’ll be taking on as ABIM’s President and CEO. I’m heartened to lead an organization that provides many physicians with the same opportunity: to demonstrate on a level playing field their medical knowledge with a national standard set by peers in their discipline upon which our profession and patients everywhere can rely.

At the same time, I also recognize just how much has changed in health care and at ABIM in the last 10 years. I am proud of how our programs have evolved, such as the Longitudinal Knowledge Assessment (LKA®), so that they work better for practicing physicians. I am also keenly aware that we need to balance how frequently those changes occur, so that physicians can have time to understand and experience the programs for themselves and help us evolve them most relevantly in their disciplines.

As I prepare to take on this new role, I want to share my deep appreciation for those who helped guide me throughout my life and career. I’ve always been a big believer that one’s best work is never done alone. That is particularly true in medicine and particularly true for me. I’ve benefited from many colleagues and mentors in the field, who took the time to sometimes gently guide and sometimes push, prod and propel me forward. I’m hopeful that those who have had such a tremendous influence in my life are reading this. Even though I’ve not mentioned your names, I hope that you know who you are and how much you’ve meant to me. I hope that when given the same opportunity, I’ve been able to return the favor in kind in the past, and will be able to in the future.

From one physician to another, this is my commitment to you: I will continue listening, learning and doing all that I can on behalf of the profession of medicine, internal medicine and its subspecialties, in particular to provide a meaningful certification program that creates a level playing field and which you can feel proud to have earned.

With gratitude,

Furman