Colleagues,

It’s my pleasure to share my perspectives on three of the topics featured in this edition of “News and Notes.”

edition of “News and Notes.”

In August, I had a sneak preview of the Longitudinal Knowledge Assessment (LKA) as a beta tester of the software platform. I answered questions on my smartphone, iPad, and desktop. While not designed to evaluate the content, the beta test gave me a feel for what it will be like to answer questions in the LKA, including knowing whether I got them correct with rationales for the correct and incorrect answers. I tried the “time bank” to get extra time to answer a few questions. Based on my brief look, I think you’ll like the LKA.

As highlighted here, ABIM is exploring several areas related to diversity, equity and inclusion—and asking some challenging questions about what we as an organization can do. I find the following particularly interesting: Do race and ethnicity identifiers in exam questions perpetuate bias? Is excluding that information harmful? Two decades ago, ABIM adopted policy to stop identifying race and ethnicity in questions. In April, in follow up of its Statement on Racial Justice, the Board of Directors adopted a resolution that calls for reconsideration of that decision and authorizes research on the impact of race and ethnicity identifiers in exam questions. ABIM staff have begun to design this research. While including such information may promote better understanding of the impact of social determinants, it might reinforce stereotypes of race as a biological construct. This may be a question that does not have a single best answer.

Our Joint Statement on the Dissemination of Misinformation generated a lot of positive feedback. Like many of you, I am angered by colleagues who misinform the public about COVID-19 vaccines and treatments, undermining our efforts to keep patients safe. Understandably, some are calling for swift action and are frustrated by what appear to be slow responses.

Disciplinary actions – ABIM’s and others’ – are deliberate by design. Processes must be fair, thorough, and respect the rights of the diplomate. We will hold our colleagues accountable, but without being arbitrary or capricious.

In the meantime, public comments by ABIM, ACP, and other organizations can have a more immediate impact, as we have already seen. You and your networks can help by amplifying our messages.

There is something else that we can do. Every day, I address misinformation in the exam room when I ask patients who haven’t been vaccinated: why not? Asking the question in a way that creates a safe space for discussion shows respect and provides opportunities to inform. Our patients trust us, more than any other source of health information, to give them the facts.

There are over a quarter million ABIM diplomates. What if every day, just half of us convinced one patient to get vaccinated? That would be a pretty big number with a significant impact.

Sincerely,

Yul D. Ejnes, MD

Chair, ABIM Board of Directors

The Longitudinal Knowledge Assessment (LKATM) launches in 12 specialties in January 2022 and is included with your annual MOC fee.

As you know, in light of the ongoing pandemic, ABIM extended deadlines for all Maintenance of Certification (MOC) requirements to 12/31/22. For the four specialties most affected by COVID-19: Critical Care Medicine, Hospital Medicine, Infectious Disease and Pulmonary Disease – the extension is until 12/31/23, when the LKA is launched in these specialties.

For most physicians, now is a good time to think about how you will meet your MOC requirements, especially if you have an assessment due by the end of next year.

The good news is there are options available, including the LKA, which will launch in January 2022. The LKA is included in 12 disciplines at no extra charge under an updated fee model effective 1/1/2022.

Registration for all MOC assessments, including the LKA, opens on December 1, 2021.

If you have thoughts or questions about any aspect of the LKA, we welcome your feedback.

Physicians due for assessment in 2020, 2021 or 2022 can enroll in the LKA if it is available in their specialty beginning December 1.

The first set of questions will be delivered January 4, 2022. Enrolling early ensures you will have the full quarter to access and answer questions for that period. It’s important to start taking questions as early as you can because they’re only available for that quarter. Once the quarter ends any unopened questions will expire, and count against the 100 unopened questions you are allowed during the 5-year LKA cycle.

There are a number of benefits to using LKA for MOC:

- You can answer questions almost any place or any time using any internet-connected computer, tablet or smartphone. No need to go to a test center, though it is a good idea to find a quiet space where you can focus.

- You can access any resource you use in practice (except another person).

- You’ll earn .02 MOC points for every correct answer.

- And you’ll receive immediate feedback on whether your answer is right or wrong, with references and rationales so you can learn as you go.

Learn more on the LKA Website.

The traditional 10-year exam is also available for those who prefer it. For more information about your MOC requirements or to enroll, please visit your personalized Physician Portal.

In June 2020, ABIM and the ABIM Foundation issued a statement on Racial Justice, committing to becoming an actively anti-racist organization. In it, ABIM pledged to “analyze our programs for potential disparate impact on racial or ethnic minority candidates, be transparent about the results and address any inequity to which we may be contributing, [and to] eliminate racism, its underlying roots of power and privilege, and its impact within our organizations, our communities, and our country.”

In order to make good on that commitment, in spring 2021 the ABIM Board of Directors passed two resolutions: under the first, ABIM staff will conduct research to determine if and how inclusion of race and ethnicity identifiers impacts exam performance, as well as if and how it affects responses to questions.

The second resolution commits ABIM to researching, creating and ultimately including questions related to health equity in its assessments in the future.

What does that mean?

Rebecca Lipner, PhD, ABIM’s Senior Vice President of Evaluation, Research & Development, emphasized that there are decades of research on health equity; this research has identified disparities in health care and health outcomes in many areas. The questions that will be added to assessments will likely be discipline-specific and cover topics that physicians practicing in that field should understand in order to provide good patient care to all.

All questions that appear on ABIM assessments go through a rigorous development process. “The health equity questions will go through the process that every other question goes through,” she said. “The questions will be field tested, and will go through our whole review process. They are being treated the same way as every other question and won’t count in your score until they are proven to be fair and accurate questions.”

Dr. Lipner added that while some physicians may not have been specifically trained on health equity, they should be aware of health issues that may present differently in patients with specific backgrounds. She gave the example of women of Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry, who are at increased risk for having the BRCA1/2 gene mutations that confer an increased risk of breast and other cancers.

There are other conditions where evidence shows that some physicians provide different types of care to patients from different groups, although there is no biological reason to do so. Decades of research has uncovered inequities in care, and it is important for physicians to recognize them. As Dr. Lipner noted, “We’re not trying to trick anyone. We’re just trying to make sure people understand that there are elements in race, ethnicity, and gender that do play a role. We want to make sure they know what to ask and what to look for so they make the right diagnosis and provide the right treatment for all their patients.”

As the team makes advances in the development of health equity questions, we’ll keep you up to date about when you can expect to see questions on the exam.

If you’re interested in helping write exam questions, please visit ABIM’s website to learn more about the exam item writing committees as well as ABIM’s commitment to health equity.

As you may know, ABIM released a joint statement with the American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM) and the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) condemning the spread of misinformation about the safety or efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines by physicians, and noting that physicians who spread such misinformation are at risk of losing their certification.

In a follow-up message, Dr. Baron said, “as a community, we’ve all become acutely aware of the danger misinformation poses to our patients and profession. Too many have died or needlessly suffered from COVID because they’ve been misled by something they’ve seen on social media, often coming from someone holding themselves out as an expert. We have a responsibility—as board certified physicians who truly have medical expertise—to take decisive action and combat this rising tide of harmful misinformation.

We [made the statement] to show our support to board certified physicians, many of whom have reached out to ask for help managing the flow of misinformation coming from a few physicians.”

Learn more about ABIM’s policy and procedures on disciplinary sanctions, including unprofessional behavior such as spreading misinformation about the efficacy and safety of COVID-19 vaccines.

Your ABIM certification sets you apart and demonstrates to your peers and patients that you are an expert physician in your discipline. ABIM provides you with options for how you maintain your certification, giving you the flexibility to choose what works best for you while also giving you — and others — confidence that you are keeping your medical knowledge current

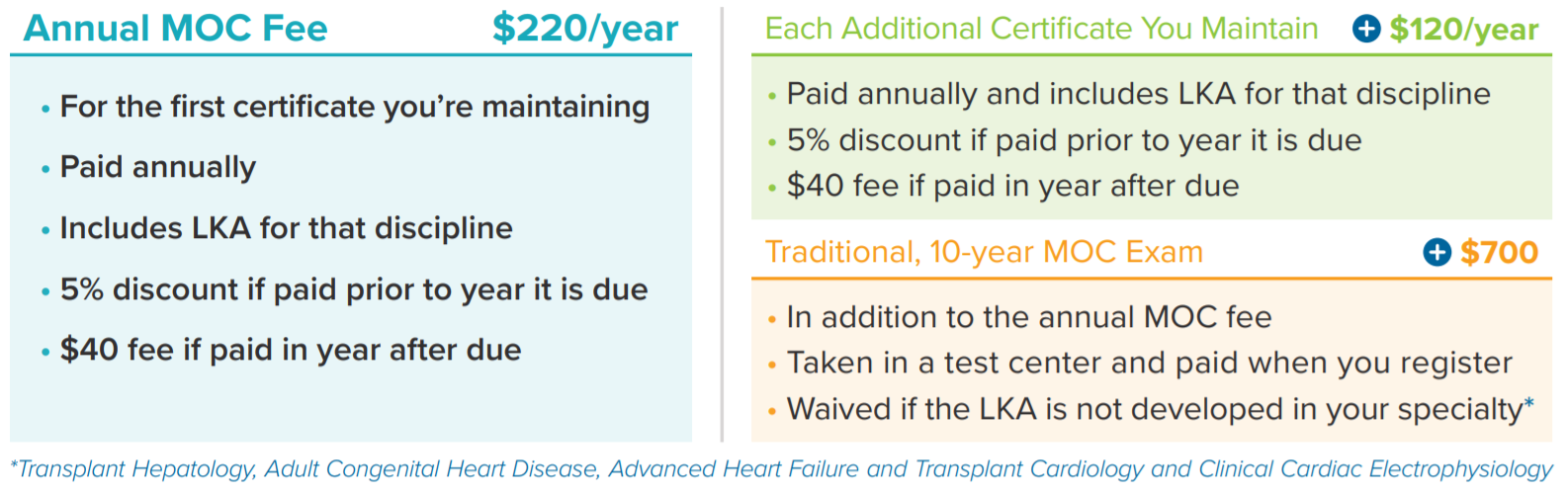

ABIM has updated the MOC fee structure to coincide with the release of the Longitudinal Knowledge Assessment (LKATM). The LKA will be included in your annual MOC fee at no additional cost, allowing ABIM Board Certified physicians to choose an assessment option that enables them to pay less as measured over a 10-year period.

The new payment structure will go into effect 01/01/22, when the LKA becomes available for 12 specialties.

If you decide you no longer want to maintain one of your certificates (deactivate a certification), you must inform ABIM by January 31, 2022 or you will be charged the certificate fee for 2022, and will be reported as ‘Certified’ in that discipline for the remainder of the calendar year. You can opt to stop maintaining one or more of your certificates by signing in to your personalized ABIM Physician Portal.

Here’s what you can expect to pay for MOC starting in 2022:

You can pay your 2022 MOC fee early and receive a 5% discount from 12/01/21 – 12/31/21. Unpaid program fees for 2021 can be paid until 12/31/21 at the regular rate, without incurring late charges.

For those with a remaining account credit from a Knowledge Check-In (KCI) or 10-year exam, you will not be charged an additional fee for your first attempt on the 10-year exam if the exam fee has increased. The entire credit will be used to pay for the exam, and a zero balance will be left on your account.

MOC helps you deliver outstanding patient care.

- Clinical Knowledge and Trends in Physicians’ Prescribing of Opioids for New Onset Back Pain, 2009-2017 published in JAMA Open. The study found that during a period of growing concern over addiction to opioids and a shift in recommended guidelines, physicians with higher clinical knowledge scores on the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Internal Medicine Maintenance of Certification (MOC) Examination wrote fewer opioid prescriptions (especially high-dose, long-use prescriptions, such as Oxycontin) for back pain than those who scored lower on the assessment. The study of 10,246 mid-career general internists suggests that those who scored higher on the assessment may have been more aware of guideline changes that warned against dangers surrounding the over-prescription of opioids for musculoskeletal pain, and reduced prescriptions accordingly.

- The Association Between Physician Knowledge and Inappropriate Medications for Older Populations published in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society (AGS). Physicians with higher scores on the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Internal Medicine Maintenance of Certification (MOC) Examination were less likely to prescribe “potentially inappropriate medications” (PIMs) to their older patients – including anticholinergics, which have been linked to cognitive impairment and decline in older patients. In younger patients, anticholinergic medications are frequently prescribed to treat colds and allergies as well as gastrointestinal, genitourinary and many other disorders. The study looked at how 8,196 general internists prescribed 72 different medications, such as tricyclic antidepressants, skeletal muscle relaxants and long-acting sulfonylureas, which are considered potentially inappropriate for older patients by the AGS Beers criteria® guidelines. The AGS Beers criteria®, which guide safe medication use in adults more than 65 years of age, advise against using certain drugs because the medications’ risks start to outweigh the benefits in older adults